- The Institute

- Research

- Dictatorships in the 20th Century

- Democracies and their Historical Self-Perceptions

- Transformations in Most Recent History

- International and Transnational Relations

- Edited Source Collections

- Dissertation Projects

- Completed Projects

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Center for Holocaust Studies

- Berlin Center for Cold War Studies

- Publications

- Vierteljahrshefte

- The Archives

- Library

- Center for Holocaust Studies

- News

- Dates

- Press

- Recent Publications

- News from the Institute

- Topics

- Reordering Yugoslavia, Rethinking Europe

- Munich 1972

- Confronting Decline

- Digital Contemporary History

- Transportation in Germany

- German Federal Chancellery

- Democratic Culture and the Nazi Past

- The History of the Treuhandanstalt

- Foreign Policy Documentation (AAPD)

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Hitler, Mein Kampf. A Critical Edition

- "Man hört, man spricht"

- Dates

- Press

- Recent Publications

- News from the Institute

- Topics

- Reordering Yugoslavia, Rethinking Europe

- Munich 1972

- Confronting Decline

- Digital Contemporary History

- Transportation in Germany

- German Federal Chancellery

- Democratic Culture and the Nazi Past

- The History of the Treuhandanstalt

- Foreign Policy Documentation (AAPD)

- Dokumentation Obersalzberg

- Hitler, Mein Kampf. A Critical Edition

- "Man hört, man spricht"

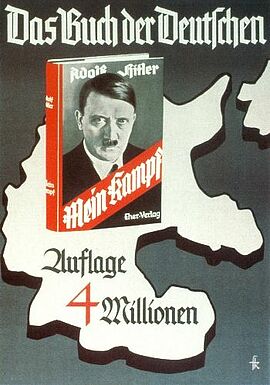

Hitler, Mein Kampf. A Critical Edition

On 31 December 2015, 70 years after Hitler’s death, the copyright will expire on his book Mein Kampf. Immediately after this expiration in January 2016, the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ) has presented a scientifically annotated complete edition. For this purpose, a team of historians led by Christian Hartmann has comprehensively edited Mein Kampf over a period of several years.

Central in critical commentary are the deconstruction and contextualisation of Hitler’s book. How did his theses arise? What aims was he pursuing in writing Mein Kampf? What social support did Hitler’s assertions have among his contemporaries? What consequences did his claims and asseverations have after 1933? And in particular: given the present state of knowledge, what can we counterpose to Hitler’s innumerable assertions, lies and expressions of intent?

This is not only a task for historiography. In the view of the powerful symbolic value still attached to Hitler’s book, the task of demystifying Mein Kampf is also a contribution to historical information and political education.

What is Mein Kampf?

Mein Kampf is Hitler’s most important programmatic text. He composed it between 1924 and 1926 in two volumes. In a strongly stylized form, Volume 1 centres on Hitler’s biography and the early history of the Nazi party (NSDAP) and its predecessor organization, the German Workers’ Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, DAP). Volume 2 mainly deals with the political programme of the National Socialists. Large sections of Volume 1 were written during Hitler’s incarceration in Landsberg am Lech subsequent to his abortive coup attempt in November 1923. Its failure, his imprisonment and the prohibition of the NSDAP interrupted Hitler’s political career. He utilised this time in order to weld everything that he had previously experienced, read and thought into an ideology in written form, and to develop a new perspective and strategy for his now outlawed party. After his release from prison, Hitler wrote much of the second volume at his mountain retreat in Obersalzberg. Once Hitler was installed as Reich Chancellor in January 1933, sales of the book skyrocketed, and it became a bestseller. Down to 1945, it was translated into 18 languages and 12 million copies were sold.

After Hitler’s suicide and the collapse of the Nazi regime in 1945, the victorious Allied powers transferred the rights to Hitler’s book to the Free State of Bavaria. The Bavarian state government had then repeatedly employed the copyright in its possession to prevent any new printing of the work. But with the expiration of the copyright 70 years after Hitler’s death, effective since 1 January 2016, this legal instrument was no longer available.

Why a critical scholarly edition?

Mein Kampf is one of the central source documents of National Socialism. Writing in 1981, the historian Eberhard Jäckel stressed its importance and impact: ‘Perhaps never in history did a ruler write down before he came to power what he was to do afterwards as precisely as Adolf Hitler. For that reason alone, the document deserves attention. Otherwise the early notes and accounts, speeches and books that Hitler wrote would at best be solely of biographical interest. It is only their translation into reality that raises them to the level of a historical source’.

Hitler’s politics, the war and crimes he initiated, changed the world completely. It was for that reason that all extant texts he authored – his speeches, his early notes and observations, his conversations with diplomats, his ‘monologues’ in the Führer Headquarters, his instructions for the conduct of the war and finally likewise his last will and testament − were published long ago. For a long time, however, there was no scholarly version of Hitler's most comprehensive and, in some ways, most personal testimony. Only excerpts of Mein Kampf were published - a gap that had long been considered a desideratum in research on National Socialism.

It was thus the aim of the IfZ to present Mein Kampf as a salient source document for contemporary history, to describe the context of the genesis of Hitler’s worldview, to reveal his predecessors in thought and mentality as well to contrast his ideas and assertions with the findings of modern research.

In preparing scholarly editions of National Socialist texts, the IfZ can point to a varied and wide-ranging expertise: for example, the collection of Hitlers Reden, Schriften, Anordnungen 1925-1933 (Hitler’s Speeches, Writings and Directives, 1925-1933), published between 1991 and 1998/2003, encompasses 12 volumes. In 1961, the Institute for Contemporary History also published Hitler’s Zweites Buch (Second Book). In the 1990s the Institute brought out the diaries of Joseph Goebbels and recently published the diaries of the NSDAP ‘chief ideologue’, Alfred Rosenberg. For that reason, it seemed only consistent that the IfZ also took up this challenge and with Mein Kampf, tackled a textual source that certainly does not present itself like other historical documents. Rather, what was necessary, along with sober and precise scholarly expertise, was a critical encounter with Hitler’s text, in sum: an edition with a point of view.

A contribution to political education

Preparing scientific commentary on Mein Kampf is not only a scholarly task. There is hardly any book that is more overladen with such a multitude of myths, that awakens such disgust and anxiety, that ignites curiosity and stirs speculation, while simultaneously exuding an aura of the mysterious and forbidden – a taboo that can prove for some commercially lucrative.

Consequently, this critical edition of Mein Kampf also views itself as a contribution to historical-political information and education. It seeks to thoroughly deconstruct Hitler's propaganda in a lasting manner and thus to undermine the symbolic power of the book. In this way, it also makes it possible to counter an ideological-propagandistic and commercial misuse of Mein Kampf.

After all, despite all the debates about republication, Hitler’s book has even before the expiration of the copyright long been accessible in a variety of ways: on the shelves of used book shops, in legally printed English translation or a mouse click away on the Internet – Mein Kampf is out there and every year manages to find new readers, agitators and commercial profiteers.

For that reason as well, the task of a annotated critical edition is to render the debate objective and to put forward a serious alternative, a counter-text to the uncritical and unfiltered dissemination of Hitler’s propaganda, lies, half-truths and vicious tirades. The scholarly edition prepared by the Institute for Contemporary History is oriented to political education, and thus consciously seeks in form and style to reach a broad readership. By means of a kind of ‘framing’ of the original text in the form of an introduction and detailed commentary, a subtext to Mein Kampf is constructed. Through these annotations, it quickly becomes clear how Hitler’s ideology arose, just how selective and distorted his perception of reality was, and and it becomes possible to show the link between its formulation in Mein Kampf and the political practice and its terrible consequences after 1933.

How do the editors work?

Two historians, under the direction of Christian Hartmann, are currently at work in the IfZ on the critical edition of Mein Kampf. They are structuring the original text by providing explanatory introductions to each individual chapter; through more than 3,500 annotations, they address a broad spectrum of variegated tasks by providing:

- Objective information on persons and events described

- Clarification of central ideological concepts

- Disclosure of the source materials Hitler utilised

- Explanation of the roots of various concepts in the history of ideas

- Contextualisation of aspects contemporaneous to the text

- Correction of errors and one-sided accounts

- Development of a perspective on the consequences of Hitler’s book

- New contributions in relevant fundamental research

Unusually in the context of an edition of a book, the editorial team is also examining the period after 1933, thus comparing Hitler’s programmatic ideas with his political actions in the time period 1933-1945.

The core editorial team, which in the peak phase of its work on the edition consisted of five historians, was further supported by experts from a number of other scientific fields in order to better evaluate Hitler’s myriad assertions in the light of the findings of modern research. To that end, external interdisciplinary advisors have also been consulted from a range of scholarly disciplines, including German Studies, human genetics, Japanology, Jewish Studies, art history, the educational sciences and economic history.

The team at the IfZ also encompassed special editorial staff for copy-editing and manuscript preparation, indexing and the precise textual comparison of seven select printings of Mein Kampf, along with a number of student assistants. Besides, the team was additionally able to benefit significantly from the broad professional infrastructure of the entire IfZ, with its many staff members specialized in research on the period of National Socialism, and its wealth of relevant library and archival resources.

Print edition and online version

After the successful publication of the two-volume edition, many people expressed the wish to make it accessible online as well. Since July 2022, the IfZ has therefore also made its critical edition available in a free online version, going far beyond a mere e-book form: Like the print version, the online edition is intended to make Mein Kampf usable as a source for scholarly work and, with its technically advanced search functions, to enable new methods of analysis. At the same time, however, the online edition of the IfZ once again sends an important signal: free of charge and thus accessible to all, it counters the Mein Kampf versions from mostly very dubious sources that have been circulating on the Internet for a long time with a serious, scholarly reference point and, thus, provides political-historical enlightenment in the best sense.